Mosaic in Chagall’s Monumental Work

Quitterie du Vigier

Introduction to the Mosaic Work1

“I’m looking for a large wall,” Marc Chagall said in the 1960s.2 In 1973, the art magazine xxe siècle3 devoted a special issue to “Monumental Chagall”. Etymologically, the idea of “monumental art” refers to a “historic, timeless dimension” intrinsically linked to the idea of memory and “spatial notions of great size.”4 “This is an adjective that should frighten Chagall a little,” said editor San Lazzaro with a touch of humor, adding that the magazine would not be devoted solely to the “painter of great buildings” but more broadly explore the “monumental” in the artist’s body of work: Here, “monumental” primarily means “eternal”.

Chagall’s monumental adventure began just after the Second World War when, back from his exile in the United States, he settled in the South of France and branched out into sculpture, ceramics, stained glass, tapestry and mosaic. However, its roots go back much further, as Guillaume Apollinaire mentioned when writing about the monumental character of Chagall’s paintings as early as 1914: "He is an extremely versatile artist capable of monumental paintings. No system stymies him.”5 Chagall’s early 1920s set deigns for Moscow’s State Jewish Chamber Theatre (GOSEKT)6 exemplified his “inner need to exceed the limits of the painting”.7

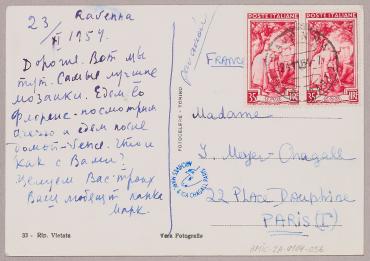

Mosaic, with its roots in Antiquity, commanded the artist's admiration as early as 1948. In a letter to his daughter Ida while visiting Venice that year, he expressed his amazement at the mosaics in Santa Maria Assunta cathedral on Torcello Island8. In 1954, on another trip to Italy, he sent her a postcard of the Byzantine mosaic in the apse of the basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna.9 This interest led him to collaborate with Ravenna’s Gruppo Mosaicisti, with Lionello Venturi as an intermediary10 and at the invitation of Professor Giuseppe Bovini,11 who wanted to exhibit mosaics by contemporary artists.12 The first two, The Blue Rooster (1955-1958),13 were based on a gouache by the artist.14

Chagall designed 28 mosaics as part of 14 different projects carried out between 1955 and 1986, first by Lino and Heidi Melano,15 then Michel Tharin. One was posthumously transposed by Heidi Melano after the lithograph The Green River (1974).

Mosaic: a monumental art

In 1937, Chagall was a card-carrying member of Art Mural,16 an association whose main aim was “to promote demonstrations of mural and outdoor aesthetics and techniques through annual exhibitions.”17 Not surprisingly, then, in the late 1950s the multidisciplinary artist undertook a series of large-scale architectural projects integrating his “mosaic work”. Chagall’s monumental pieces were created in the context of postwar France, with a surge of government contracts starting with 1945,18 and the implementation in 1951 of the “1% art scheme”19, which funded the The Message of Ulysses, School of Law and Economics, Nice [Le Message d'Ulysse, Faculté de droit et des sciences économiques, Nice] (1967 - 1969) mosaic.20

Influenced by his exploration of materials and the light of southern France, the artist constantly pushed back the boundaries of painting. Color, too, became “monumental”21 Chagall was commissioned to create several works for buildings. He enjoyed fostering dialogue between the various techniques with which he experimented in the same architectural setting, whether sacred or secular, indoor or outdoor. Through this dialogue, he redefined the perception of monumental art and the integration of his works in space, as attested by his project for the Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce church baptistery on the Assy Plateau, commissioned by Abbot Jean Devémy and Father Marie-Alain Couturier. It furthered the goal of “renewing sacred art” by incorporating a large ceramic piece22 (The Crossing of the Red Sea, 1956), two marble bas-reliefs (The Bird, or Psalm 124 and The Doe, or Psalm 42, 1957) and two stained-glass windows (Angel with Candlestick andAngel with Holy Oils, 1956-1957) into religious architecture.23 Drawing on this experience and his early work in mosaics, in 1964-1966 Chagall designed what is known today as the “Cour Chagall”, the inner courtyard of his friends Georges and Ira Kostelitz’s home on rue de l'Élysée in Paris. He created a harmonious setting featuring mosaics on three walls and two sculptures.24

Later, Chagall continued to explore combining different artistic techniques for public buildings. In a letter to Chaim Weizmann, the first president of Israel, he wrote: “I have dreamed of working on public walls for a long time.”25 In 1960, at the same time that Chagall was designing the stained-glass windows for the Hadassah hospital synagogue in Jerusalem, Knesset president Kadish Luz wrote to the artist about a plan to decorate Israel’s future parliament building.26 The Wailing Wall, the large wall mosaic that hangs on one of the picture rails, is in the same room as 12 floor mosaics recalling ancient Roman mosaics, as well as three Gobelins tapestries: The Creation, The Exodus and The Entrance to Jerusalem.27 In France, the construction of the Biblical Message museum to house a painting cycle begun in the early 1950s and given to the French government in 1966 marked another major step forward in Chagall’s monumental work, which was celebrated in a 1974 show.28 Architect André Hermant designed the building. Here, Chagall again created dialogue between different media by designing stained-glass windows for the auditorium (The Creation of the World, 1971-1972), a tapestry (Mediterranean Landscape, 1971) and a mosaic, The Prophet Elijah, or Elijah’s Chariot, Musée national Marc Chagall, Nice [Le Prophète Élie ou Le Char d'Élie, Musée national Marc Chagall, Nice] (1970 - 1973). Commissioned for the museum by the French government, the mosaic was completed by Lino Melano in 1972 with the help of Michel Tharin. It features the prophet Elijah on his chariot surrounded by the 12 signs of the zodiac, overlooking a pool.29

The mosaics’ genesis and the monumental creative process

Various public and private clients commissioned Chagall's mosaics, which attest to the very different contexts in which they were created. In 1964, he designed a mosaic for the Marguerite and Aimé Maeght Foundation, inaugurated on July 28, 1964.30 The Lovers, Marguerite and Aimé Maeght Foundation, Saint-Paul-de-Vence [Les Amoureux, Fondation Marguerite et Aimé Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence] (1963 - 1964), depicting two people with their heads together surmounting a single body, marked the start of Chagall’s collaboration with Lino Melano, who made a test for this first mosaic.31 In 1946, Chagall met John Nef in Chicago. His friendship with him and his future wife Evelyn subsequently led to the commission Orpheus, home of John and Evelyn Nef, Washington, DC [Orphée, maison de John et Evelyn Nef, Washington DC] (1968 - 1971), a mosaic for an outer wall of their home in Washington.32 For a wall of the terrace at his Saint-Paul-de-Vence house and studio, Chagall chose a luminous iconographic motif that transcended several of his creations: The Large Sun, La Colline Villa, Saint-Paul-de-Vence [Le Grand Soleil, villa La Colline, Saint-Paul-de-Vence] (1965 - 1967)33 attests to the importance of mosaic in the artist’s Mediterranean career and daily life.

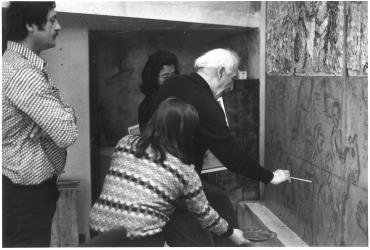

Whenever he tackled a new medium, Chagall trusted the craftsman's know-how and relied on talented collaborators. Like stained glass and tapestry, the creative process for mosaic is based on transposing a model, in this case entrusted by Chagall to Lino and Heidi Melano and, from 1973, Michel Tharin. Chagall made sketches and models in different formats and integrated collage34 into painting, recalling Cubism.35 Paper and fabrics specified the desired shapes and chromatic nuances, introducing the play of textures and materials at the heart of his approach. This process was not confined to mosaics, but also used for the stained-glass windows at the Hadassah hospital synagogue in Jerusalem (The Tribe of Issachar, definitive model for the stained-glass windows at the Hadassah hospital synagogue, Jerusalem,1959-1960); the new ceiling for the Garnier opera house in Paris36 (definitive model for the Paris opera house ceiling, 1963); and the murals at New York’s Lincoln Center (definitive model for the Metropolitan Opera mural, Lincoln Center, New York: The Triumph of Music, 1966).37

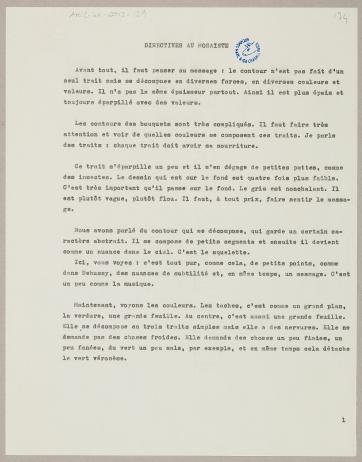

In the first, undated, “guidelines for the mosaicist” and the second, sent to Lino Melano in 1964,38 Chagall tried to convey his vision of line and color to the craftsman to help him understand what he wanted as best as possible: "Most of all, think of the message. The contour is not a single line, but broken down into various forces, colors and values ... In mosaics, I look for atmosphere". Chagall, considered by Malraux to be “one of the leading colorists of our times”,39 sought to communicate his command of color with regard to the technical specificities of mosaic, especially the juxtaposition of colored tesserae: “How do the spots look when they come up against each other? That is what you must pay attention to. Look at the thousands of spots you can make out. Do they get along with each other? How do they behave with their neighbors? Are there arguments? That’s what it’s about.”

Chagall’s collaboration with the Melanos ended in 1973, after a fire in their Biot studio destroyed some of the models for his most ambitious mosaic project, The Four Seasons, a gift to the City of Chicago. Several sketches and gouaches on the same theme were exhibited at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1975.40 The monumental project was brought to a successful conclusion by Michel Tharin, with whom Chagall collaborated on his last mosaics: The Angels’ Meal, Saint Roseline Chapel, Les Arcs-sur-Argens [Le Repas des Anges, Chapelle Sainte-Roseline, Les Arcs-sur-Argens] (1974 - 1975), and Moses Saved from the Water, Notre-Dame de la Nativité Cathedral, Vence [Moïse sauvé des eaux, Cathédrale Notre-Dame de la Nativité, Vence] (1979). The abundant correspondence following the inauguration of The Four Seasons, First National Bank Plaza, Chicago [Les Quatre Saisons, First National Bank Plaza, Chicago] (1971 - 1974) attests to its success: “Your gift is one of permanence and constant joy,” Gaylord Freeman, president of the First National Bank of Chicago, wrote to Chagall.41

In the United States and other countries, Chagall and the artisans with whom he collaborated fully contributed to the 20th-century renewal of mosaic. This age-old art form was the artist's response to the visual explorations that characterize his monumental work, bringing together the richness of materials, color and light in resonance both with the architecture and its specific features, and with the surrounding landscape, thus reshaping it.

Originally published in the catalog De pierre et de verre. Chagall en mosaïque © GrandPalaisRmn, Paris, 2025.

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall.