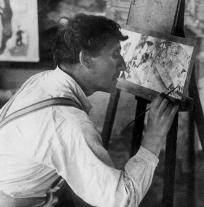

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

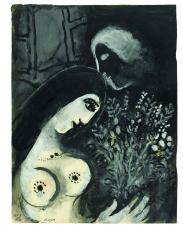

One of the first bouquets immortalized by the artist appears in View from the Window in Vitebsk, 1908. A vase of shimmering flowers is placed on the windowsill, like a manifestation of the painter’s luminous gaze as he looks out from the comforting intimacy of his bedroom onto a shining rainbow symbolizing peace and joy. The first depictions of flowers in Chagall’s works were inspired by the presence of Bella Rosenfeld, whom the artist met in the summer of 1909. In particular, an elegant, colorful bouquet that Bella gave him was the starting point for the celebrated painting entitled Birthday, 1915, full of loving jubilation.

Upon Chagall’s return to France, in 1923, a profusion of flowers was blooming in the space shown in the painting. Often depicted in an outdoor environment, they formed a sort of “link between the painter and a new landscape” (Jackie Wullschläger), becoming a way for the artist to ground himself in his quest for a new identity in his adopted country. His immersion in natural landscapes during several journeys around France, as well as his revelation of new colors, were manifest in his study of flowers: “The abundance and variety of flowers was a source of wonder and fascination for me. [...] For many, this profusion of flowers helped develop the palette of the best French artists” (Marc Chagall). For Chagall, recognized during his lifetime as a grand colorist, the French painters (especially the impressionists) were the most highly skilled at using “floral pigment,” thereby working a “chemistry” so dear to the artist: breathing life into color.

Expertly arranged in hundreds of compositions, Chagall’s flowers are spread throughout his works and come to life. Never confined to the role of being “just” accessories, Chagall’s bouquets are meaningful, even personified, as with the floral “portrait” in Flowers on a Chair, 1926. An expression of what cannot be expressed, of a deep sentiment tying the artist to the world and to himself (see Peace or the Tree of Life, 1976, stained glass, Cordeliers chapel in Sarrebourg), flowers are also a sacrificial figure in times of war and menace: “The poor and innocent weren’t the ones who should have been thrown in prison. Rather, the flowers of Nice, devastated and orphaned, should have been tossed in the kilns instead. Those people don’t need flowers” (Marc Chagall). Established in the South of France starting in 1951, Chagall was fascinated by the Mediterranean light and lush vegetation. Produced using the full range of techniques explored by the artist, flowers—flaky, sparkling, vibrant, exalted—stayed with him and transcended him throughout his body of work.