Marc Chagall’s Sculptures

Ambre Gauthier

The ‘geology-genealogy

In November 1949, Marc Chagall moved from Orgeval to Vence, living first in a villa called “Le Studio” before moving to another villa, “Les Collines,” in 1950. Les Collines was a space devoted to “sculptures, pottery, and various messy procedures1.” Like Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, Chagall’s move to the Mediterranean after the war coincided with a need for personal and artistic renewal. It was a turn towards light and radiance, which comes through in his work as an exploration of techniques he hadn’t yet experimented with. His words convey the visual and sensory shock triggered by these new horizons: “As I drew closer to the Côte d’Azur, I felt a sense of regeneration—something I’d forgotten since childhood. The smell of flowers, a new kind energy was flowing into me2.” In the south, Marc Chagall took his art’s temperature with his “eye-thermometer3,” plunging his hands into clay and confronting the facets of the rock he attempted to tame. He was seeking materials that would anchor him to his adopted land4 while speaking to his imagination through their intrinsic qualities. “Gossiping with the clouds5” and interpreting their shapes with eyes looking up to the sky, seeing the contours of dancing figures in the cavities of Jerusalem stone, and scrutinizing golems6 as they came to life in rivers of clay were the games of the imagination that we can envision him devoting himself to with passion and a spirit of mischief. The sculptures he created were a manifestation of the duality of his quest to anchor himself to the land but also to take flight, to create art that was “as simple as a cloud7.” This came through in his choice of subjects and materials, in the telluric yet cloudy shapes of carved marble.

Seeking an “organic truth8,” in the words of Germaine Richier, he began exploring materials through various techniques (ceramics, sculpture, stained glass, and mosaic) that developed and grew richer at the same time. In 1949, his first trials in ceramic were carried out at the pottery works of the Ramparts of Antibes9, while the first sculptures were carved in 1951, although it appears the idea was born in 195010. Stone became an obligation for him starting with the journey to Palestine in 1931, where “only two paths were open to [him]: taking the stones of this country and bashing [his] head with them, or going back as silently as [he] had come, as if nothing had ever happened11.” From the millennia-old stones of the Wall of Sorrow to the rocky slopes of the Mount of Olives, a winding path towards stone and its deep sonorities came into view, because “unlike flowers that wilt, rocks stay and speak the force of memory. They recount the unchanging place inhabited by those who have passed on in the lives of their survivors12.” Stone, a raw memory, is a gateway to the voice of the ancestors and a mineral testimonial to past history. For Marc Chagall, this amounted to a kind of “geology-genealogy” through which memories and experiences made up the strata of the rocks.

His decision to work with clay and stone was also a decision to anchor himself in a millennia-old practice in order to saturate himself in the history of a country, become one with it, and attach himself to a land to get off to a new start. The joint development of the practice of sculpture and ceramics allowed Chagall to symbolically and artistically position himself as an artisan, a maker, to shape natural and ancestral elements. The earth of our ancestors is also, symbolically, that of the hearth, which links Chagall to the white Russia of his childhood in Vitebsk. Mother Earth, the earth we cultivate, dwell on, work with, and share with others. Earth as a material we knead, mold, and transform to create ceramics, sculptures, and walls for our homes. But also the earth before which “we must be humble [...], subject!” and which makes us humble in the face of the force and immensity of nature: “What do I bring, through ceramics and sculpture, to God’s earth, to God’s fire, to the leaf, to bark, to light? Maybe the memory of my father, my mother, my childhood, and my loved ones for a thousand years... maybe also the memory of my heart13. »

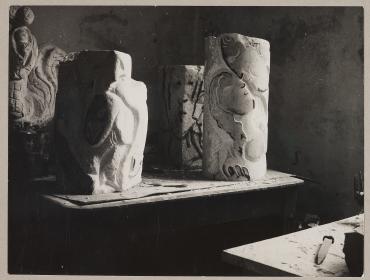

Sculpting stone

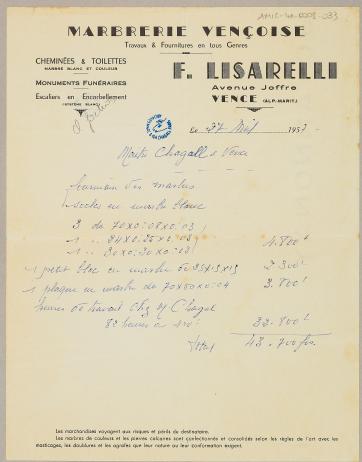

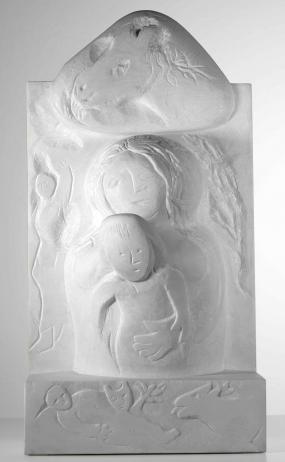

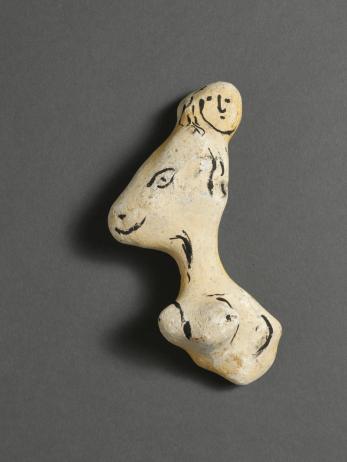

Chagall’s work with stone gave rise to a collection of sixty-five sculptures14, revealing a range of techniques and materials. For stone-carving, Chagall partnered with marble worker and carver Lanfranco Lisarelli (1913-2005), whose studio was located across from Chagall’s villa in Vence. From 1951 to 1983, with a gap between 1973 and 1980, the two men engaged in a dialogue of sculpture, which led them to experiment with various sculpting techniques (e.g. low- and high-relief, in the round, plates), all the while focusing on the quality of the stones they worked with. The choice of stones, which was a deciding factor in Marc Chagall’s approach to sculpture, was based on color, shape, and texture, and prioritized stones with “accidents.” “For me, shapes become accidents. It’s tragic. You see another world. Everything is torn apart—and yet pure. When you can’t sleep at night, you think about those accidents15.” Roughness, irregularities, cracks, and chips in the rock brought the artist closer to the “organic truth” of imperfection, which brings the material to life and makes it an ideal medium for projections and images, because “what counts isn’t the medium, the shape or the informal, the figuration, or the abstraction. What counts is the raw material16.” The artist also maintained the stones’ cavities and natural shapes, which he skillfully––and sometimes humorously–made use of, perhaps to create a nose, a mouth, or a body. He worked with each block’s original shape, just like the cave painters whose power and vital essence he admired. Lisarelli, who taught Chagall about technical and aesthetic characteristics, also helped him choose stones, driving him to local quarries and later ordering blocks17 of Carrara marble, shelly limestone, Rognes or Gard stone, and Jerusalem stone.

Using a similar process to the one he used for his ceramics, Chagall produced preparatory drawings on paper or tracing paper18, with Lisarelli carving the block selected. More rarely, he produced a pencil drawing directly on the block to be sculpted, as we see on the non-carved Lovers With a Rooster [Les Amoureux au coq] (circa 1968 - 1969): “[Chagall] visualized animals, trees, and lovers. He traced shapes onto the blocks in pencil before describing to the stone carver the relief he was aiming to achieve. Our neighbor obtained incredible results, understanding a little more each day what Marc wanted. They created a collection of low-reliefs in that way19.” The artist “rarely handled the chisel himself; he would just add details to the main shapes that had already been carved into the blocks20.” At the heart of this partially delegated creative process was the artist’s desire to project the two-dimensional figures of his paintings in space, and to make his animals, lovers, and elements jump out of the blocks of stone, beyond the canvas. Arranging his sculptures in space allowed him to see the recurrent themes of the world around him unfold and come alive in his own cosmogony.

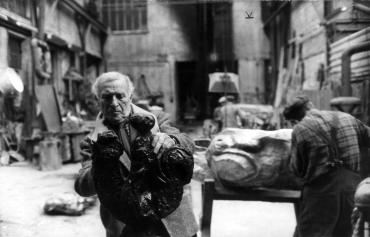

Casting bronze

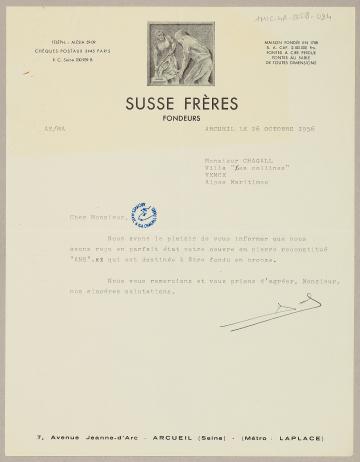

Bronze work was carried out alongside his stonework, and designed to complement his sculptural and pictorial research. The first recorded castings, which took the form of funerary plaques created by Assia Lassaigne and Yvan Goll, dated to the early 1950s. From 1956 and until 1982, a lasting collaboration developed with the Susse Fondeur studio in Malakoff, which would give rise to the 32 bronzes21. This art foundry was carried by the energy and knowledge of André and Arlette Susse, who made the production site into a space of dialogue and open creation in which “my home is the artist’s home22”. Attracted by the quality of the castings created, a number of artists followed, including Arp, Brancusi, Braque, Chillida et Giacometti. Images by the photographer Izis of the Susse Fondeur studio showed how at ease Chagall was as he occupied the premises, touching up the patina on bronzes in the presence of the foundry’s employees. Molded with the lost wax method, Chagall’s bronzes were created using plaster models which allowed the artist to place and visualize in space the shapes and iconographic elements.

Chagall’s interest for multiples (wood and copper etchings, lithographs) is also evident in his experiments with bronze castings. His investigations into nuance through applying patinas to the surface demonstrate the subtlety and variation of this work. Certain sculptures, such as Lovers With a Bouquet [Les Amoureux au bouquet] (1951 - 1952) and Rooster-Woman [Femme-coq] (1952) comprise several materials, from shell-studded limestone to marble, so the artist could explore a theme’s potential treatments through different techniques and materials.

Sculpture, a living memory

Perceiving the block of stone or bronze as a vivid memory, Chagall drew upon art from centuries gone by, turning his focus towards Russian folk art, Etruscan art, Roman art, Khmer sculpture, and even Indian art23. The books in his library bear witness to this unbounded vision, which emphasized the materials’ primary strengths, shapes, iconographies from centuries past, and also carving techniques. Chagall prioritized a tangible and sensory approach to materials because “in art, I don’t believe in technique; it’s within us24. In 1952 and 1954 he made trips to Greece at the instigation of the publisher Tériade. This allowed him to see with his own eyes Greek architecture and sculpture, which he said exceeded “all art from all peoples25”. The dazzling white Parthenon stones and the silent walk of antique kouros provided inspiration of hieratic figures with the silence of a thousand years, from dreaming Eves to the archaic smile. Among the various nourishing sources he drew upon, it is appropriate to mention Roman art. For example, the use of Rognes stone and the deliberately rough Landscape and Couple With a Bird [Paysage et Couple à l'oiseau] (1952) immediately recall the dense and compact shapes of ninth- and tenth-century sculpted chapiters. Couple With a Bird or Lovers on a Rooster or Lovers and Rooster [Le Couple à l'oiseau ou Les Amoureux sur le coq ou Les Amoureux et le Coq] (1952) low-relief, with heightened shapes and dancing arabesques, shows a deep knowledge of ornaments from Khmer sculpture and the Preah Ko style (nineth century), along with the intricate carved pediments of the Banteay Srei temple in Siem Reap (tenth century)26. Adam and Eve’s dancing bodies wrap around one other with the same flexibility as the yakshinis and shâlabhanjikâ found in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Indian art.

Via these cultural crossroads was born a universal language, borrowed from previous civilizations, through which the artist sought to write a continuous story of shapes across the continents, always paying close attention to his expression and sensitivity: “I went to Baron von der Heydt’s sculpture museum in Zurich27. On every piece exhibited we could have made the same link between Hasidic Judaism and an African sculpture28.” This shared language seemed to make him lose sight of his mission with modern sculptors, about whom Chagall expressed his reluctance: “Save a few rare exceptions, twentieth-century sculpture has not achieved the power and delight of the prayers expressed in sculptures by ancient peoples29.” He was against what he called “dependence on natural stones30,” which consisted of designing the sculpture in order to accentuate the material, to the detriment of the subject and the process of experimenting with sculpture. However, Henri Laurens and Brancusi were cited on several occasions in his writings, since Chagall admired their formal style and choice of materials31, although he did feel their approach was reductive at times: “It’s nice to discover the natural charm of a stone that’s polished in the shape of an egg, or the elegance of a piece of wood32.” However, it is interesting to note that Chagall also incorporated painted stones and driftwood into his work, where he, too, was exploring the intrinsic qualities of materials found in nature, enjoying them and repurposing them with humor. In the painted stone Ass-Woman and Face (circa 1967), he made use of the eroded shape to create a double object—an animal head and a female body. The composite Mockup for Madonna With Donkey [Maquette pour La Madone à l'âne] (circa 1968 - 1971), which served as a preparatory work for the Madonna with Donkey or Mother and Child [La Madone à l'âne ou Mère et Enfant] (1968 - 1971), combined a stone with a porcelain insulator for a highly contrasting aesthetic effect.

A multidisciplinary approach

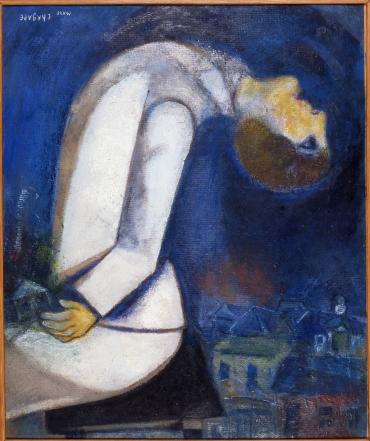

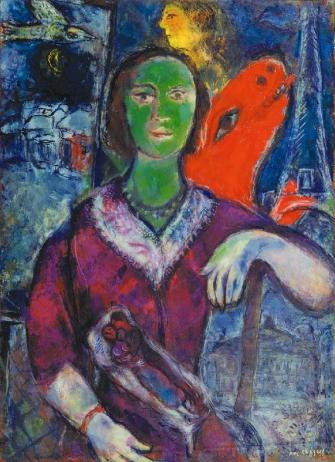

The creative dynamics for sculpted work relied on Chagall’s personal rhythm, which saw him alternate periods of intense work with breaks, depending on the works and monumental commissions to be made33. In 1952, the Maeght gallery in Paris organized an exhibit entitled Céramiques, sculptures et Les Fables de La Fontaine34 (Ceramics, sculptures and La Fontaine’s Fables) and from that point onwards began to market the artist’s sculptures35. The magazine Derrière le miroir (Behind the Mirror, n° 44-45) came out along with the exhibit and printed Lovers With a Bouquet [Les Amoureux au bouquet] (1951 - 1952) on the page facing Gaston Bachelard’s text “La lumière des origines” (The Light of Origins). The works were immediately successful, and New York’s Curt Valentin Gallery36 also exhibited them the same year. These exhibits, which took place shortly after Chagall’s initial sculptures, attest to the popularity of the art market and the criticism for this production. Such exhibits were included directly in the multidisciplinary area, in which the works engaged in a dialogue. The wide variety of techniques was not the only thing this hanging arrangement brought to light. It put sculpted works back within their own dynamic, and within the creative spirit that was Marc Chagall’s, through experimentation with several techniques at the same time. The artist was juggling with an admirable exuberance and a spirit that zig-zagged37 between themes and materials. A formal and thematic procedure was created between sculpture and painting, which moved back and forth between themes and recurrent motifs in Chagall’s pictorial work. Birthday [Anniversaire] (circa 1968), for example, resumed a 1915 composition38, with the low-relief method allowing a rougher treatment and accentuating the narrative sequence. This also gave rise to an oil-on-panel based on the same theme in 196939. The recurring motifs of the kiss and the thrown-back head also emerged in the sculpture Two Heads With a Hand or Two Heads, One Hand [Deux têtes à la main ou Deux têtes, une main] (circa 1952 - 1953) where the sculpting allowed Chagall to create a 3D version of a signature figure that symbolized ecstasy in the Hasidic tradition and the union of bodies with the divine, which had been present in his work since the 1910s. Likewise, the Vava [Vava] (1968 - 1971) sculpture found its pictorial mirror in Portrait of Vava40 (1966), announcing formal monumentality, the chisel work of the profile, and the hieratic dimension of the sculpted portrait. Two Nudes or Adam and Eve or Column Sculpture [Deux nus ou Adam et Ève ou Sculpture-colonne] (1953), where the interweaving of the bodies attempts to portray the complementarity and/or duality of the sexes, already expressed in the work Homage to Apollinaire or Adam and Eve41 (1911-1912), demonstrates this continuous circularity of influences. Thus, the search for the sculpted volume, which can be seen in Two Nudes or Adam and Eve or Column Sculpture [Deux nus ou Adam et Ève ou Sculpture-colonne] (1953), gave rise to compositions where the body occupies a central space, monumental and powerful, taking ownership of the compositions. Red Nude (1954-55) was testament to this new priority given to volumes of flesh their inclusion in a rotating space where the body is an axis, thus recalling pillar sculptures and contemporary stelae.

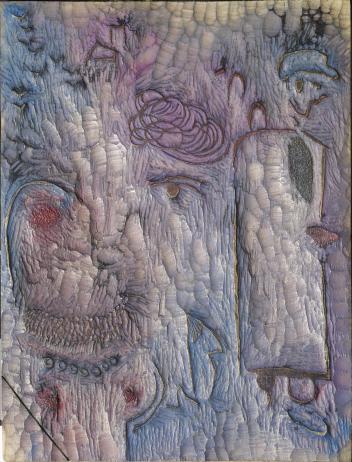

The low-relief work, through which incisions and reserves were on show, gave a new direction to Chagall’s painted work, and also to the engraved wood and monotypes he was working on at the same time. The narrative element that’s specific to low-relief work, which appears in his work through unfolded parchment paper, is a guiding principle of his creation, and is found in his first works for the stage, notably Introduction to the Theater of Jewish Art42 (1920). The low-relief medium allowed him to highlight the narration, to explore in a different way the juxtaposition of actions and times, solidness and hollowness, bringing together the Haggadah’s43 illustrated manuscripts and the Romanesque chapiters’ density. Taking Down the Cross (1952) and Women of the Bible (1969-1970) bear witness to artist’s heightening of this syncretism and narrative function, replicated in his graphic and painted works of the 1960s and 1970s. Commedia dell’arte (1959), created for the foyer of Frankfurt Theater on the theme of the circus, materializes this narrative deployment and the structuring of space as a metaphor of the world. On these works—frescoes that juxtaposed the recurring topoi (Vitebsk, Jerusalem, and Saint-Paul-de-Vence) and simultaneous actions—the characters’ silhouettes are carved into the background, in the manner of sculpted and chiseled work. Like photographic film, the Travelling People45 (1968) composition also plays on a narrative sequence and gives rhythm to the space using blank areas interspersed with shapes carved into the background, which resonates with both low-reliefs and collages on contemporary paper. The engraved wood, necessary for completing the Poems etchings that were commissioned by Cramer publishers in 1968, also constituted an extension of low-relief on an organic material with a confined format. The graphic surfaces, along with the deep incised lines and the fact that the background is filled in with patterns created by the chisel marks in the wood, evokes the contemporary sculpturing of works, from Rooster Woman (1968-1969) to Lovers With Village (1968). Paintings, monotypes, and temperas also bear the print of this technique, through a medium worked by the artist with the back of the paintbrush, which modulates the lines that are incised, scratched, or dug on the surface, showing this plurality of influences and their interpenetration in his 1950-1970 works.

Access the search for sculptures in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall