From the sketch to the completed work: Chagall, the ceramicist.

Quitterie du Vigier

The late 19th century saw the birth of “artist's ceramics”1 as the Arts and Crafts movement and Symbolist painters2 blurred the boundaries between the minor and major arts. In France, ceramist André Metthey introduced Nabi and Fauvist artists such as Maurice Denis, André Derain and Henri Matisse3 to the art of earth and fire. In 1947, Pablo Picasso began working with Madoura in Vallauris, prompting other artists to follow suit and burnishing the studio’s reputation. Chagall, a multi-disciplinary artist, began his ceramic work in 1949 shortly before turning to sculpture. He collaborated with several studios in the South of France, including Madoura. To date, over 30 preparatory sketches for his ceramics are known to exist.

Making sketches was often part of Chagall’s creative process, not only for ceramics but also for paintings (Self-portrait with Seven Fingers), theater and ballet sets (for the Jewish Chamber Theatre in Moscow and later the ballets Aleko and The Firebird) and monumental projects (the ceiling of the Paris opera house). Italian Renaissance artists were the first to theorize about preparatory sketches. The word derives from schizzo, a term used in mid-15th-century Italy to mean a “provisional drawing ... in contracts between artists and patrons”. Preparatory works may be deemed less worthy than finished paintings, but they are crucial to understanding an artist's work and have spawned a new discipline: the study of creative processes (inspired by the “genetic criticism” of literary manuscripts), which focuses on “preparatory drawings, sketches, studies, notebooks ... and notes”.5

Chagall’s earliest sketches for his ceramics probably date back to the early 1950s. Despite bearing precious witness to his imagination and creative process, they have not been closely studied to date.

He made 40 sketches6 for ceramics on a variety of supports: small-format smooth notebook pages, paper of varying sizes and tracing paper. By drawing the volumes on paper that later took shape in clay, the artist documented the transition from two to three dimensions. The sketches allowed him to work out the composition, color schemes and shapes of the ceramics beforehand.7

The sketches were hardly ever exhibited, but a 1962 Madoura Gallery show featured 20 of them face-to-face with 33 ceramics Chagall made in collaboration with the studio. In their preface to the catalogue, Suzanne and George Ramié wrote, “Aren't these works poems? ... In our eyes, most of the ones here have the privilege of being akin to our children: we have seen them come to life in our Vallauris studios, from the sketches (whose study we reveal) to the clay that gave them volume.”8

For Chagall, ceramics was where painting and sculpture came together.9 “Chagall picked up the technique in no time,” Jean Leymarie said. “At first, he just painted the finished piece. But he soon felt the need to grapple with and shape the material itself. His ceramics thus became true ‘sculptures’, which later led him to sculpture in the strict sense of the word.”10 Most of the sketches that have come down to us were made for vases or shaped pieces, which Chagall also called “vase-sculptures”.11 Shaped, turned or cast pieces require more design than a pre-existing form. The preparatory drawings, comparable to the ones used for monumental works such as stained-glass windows and tapestries, foster dialogue with the artisan. In some cases, such as Sketch for a Ceramic [Esquisse pour une céramique] (1962), the composition was plotted out on a grid. There are also sketches for dishes and a preparatory gouache for the wall ceramic Fish [Le Poisson] (1952). Some works, such as Sketch for a Dish (1954), probably never saw the light of day.

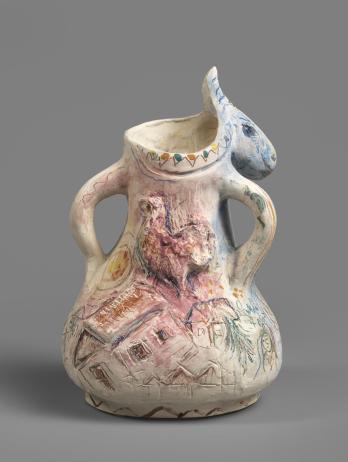

Photographs of Chagall at work show a serious-minded artist putting his "hands in the clay”12 and decorating pieces. While Chagall collaborated with studios and sought out the skills of local artisans, he designed the most sculptural forms himself, as shown by his sketches for the various versions of The Blue Donkey including Sketch for the Blue Donkey [Esquisse pour L'Âne bleu] (1954). His inspiration flowed from many sources, including Russian folk art and pre-Columbian art. He enjoyed fostering dialogue between the zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures of the form itself and the decor. His mastery of color became clear the moment he applied it to sketches.

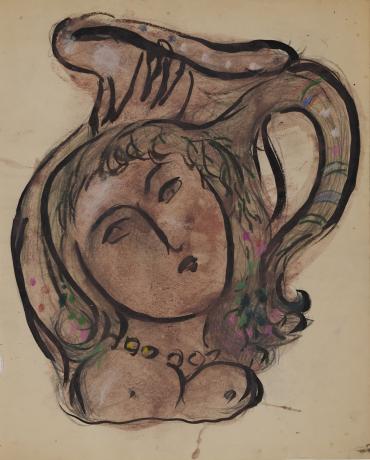

It is fascinating to see how Chagall brought his future ceramics to life. The media he chose, such as pastel, charcoal and lithographic pencil, already revealed the velvety nature of the clay's surface, as he intended. In his sketch for The Flight into Egypt [Fuite en Egypte] (1952),13 the artist used contrasting dark outlines to build the volumes. Petals run around the neck and the Virgin and Child stand out slightly from the body like a bas-relief, as seen on the terracotta version. Another example of a painstaking transposition is Sketch for a Sculpted Vase [Esquisse pour Vase sculpté] (1952), whose height surpasses that of the ceramic and offers a glimpse into the future work. Chagall sketched out each part of the composition beforehand: a woman’s bust, a handle, a hand and an animal. For his Second Vase Woman [Deuxième femme vase] (1956), he drew a jug with a round belly into which a female bust was integrated. Facial details are sketchier in ceramics, but the Madoura studio’s skilled artisans faithfully reproduced the shape of the vase.

The sketches for ceramics display Chagall's inventiveness and curiosity as he breathed new life into his art, striving to master the technique and transposing his subjects and colors to take hold of a new medium, whose shaped pieces, which he first brought to life on paper, are the culmination of the successful shift from two to three dimensions.